Cognitive Security Standards — Statement of Purpose (Draft)

Why Cognitive Security Standards?

Cognitive security standards are needed because the core risk has shifted from who can access a file to what can be inferred from a set of information once it touches AI systems. In the classic security world, you can draw boundaries (networks, roles, classification levels, “don’t copy this into that tool”) and mostly trust that separation works. But LLMs collapse those boundaries by turning scattered text into a single substrate that can be searched, summarized and recombined.

That means sensitive concepts can be “leaked” without anyone ever stealing the original document: the model or an AI-enabled workflow can synthesize the protected idea from harmless-looking fragments, logs, prompts, tickets, chat transcripts, or retrieved snippets. Standards give organizations a shared way to define and measure this new kind of exposure: semantic leakage, inference reachability, and the conditions under which AI systems can reconstruct what you meant to keep compartmented.

We also need cognitive security standards because the adoption pattern is now ambient AI: models show up inside email, docs, IDEs, browsers, customer support, meeting notes, and internal search, often added faster than governance can keep up. Without standards, every team improvises, vendors grade themselves, and audits focus on familiar but incomplete controls (access lists, data labels, retention) while missing the real failure mode: meaning crossing boundaries.

A good standard would do for AI-era leakage what frameworks like SOC 2 or ISO did for earlier eras of security: define common controls, test methods, and reporting norms. It would help CISOs compare tools, help engineers build safer architectures by default, and help compliance teams document that they’re managing not just data exfiltration, but inference and synthesis risk across the full AI-enabled workflow.

Semantic Leakage and Reachability

Traditional information security assumes that separation works. We put data in compartments (HIPAA systems vs. non-HIPAA systems, TS/SCI vs. Secret, proprietary source code vs. customer-facing knowledge base) and then enforce access control at the boundaries. LLMs complicate this because they turn text and meaning into a single computational substrate. Once information is embedded into a model’s training set, a vector index, a prompt context, or a long-running memory, the question is no longer just who can access which file but what a system can infer.

My core claim is that LLMs create a reachability problem. Once a base set of facts exists inside, or adjacent to, an LLM application, the set of reachable conclusions expands nonlinearly as capability increases, context windows expand, and retrieval tools improve. This is why domain barriers (classification boundaries, privilege tiers, proprietary walls) risk being blurred and eroded, not because someone exfiltrates the original file, but because the system becomes able to synthesize the protected conclusion.

Exfiltration vs. Infiltration

To keep terms clean, this section treats semantic leakage as two distinct security failure modes.

Exfiltration risk (outbound leakage): A user emits protected information (regulated, classified, privileged, proprietary, or contractually restricted) to a data space which could be used to train future LLMs, either directly (verbatim or near-verbatim) or indirectly (paraphrase, reconstruction, high-confidence inference). This is the familiar sensitive information disclosure problem framed for LLMs.

Infiltration risk (unauthorized domain reach): An LLM reaches an information domain it should not be able to reach through reasoning, aggregation, or mosaic synthesis, such that an unclassified or low-privilege system can output conclusions that are functionally in a higher domain (for example, TS-equivalent insights) even though it never had explicit authorized access to TS files.

In other words, infiltration is not about poisoning or tampering. It is about crossing an epistemic boundary. It is the ability of the system to climb into a domain by joining and inferring across sources that were individually permitted. Both risks undermine domain barriers, but they break them differently. Exfiltration is a disclosure failure. Infiltration is a boundary maintenance failure.

Reachable information

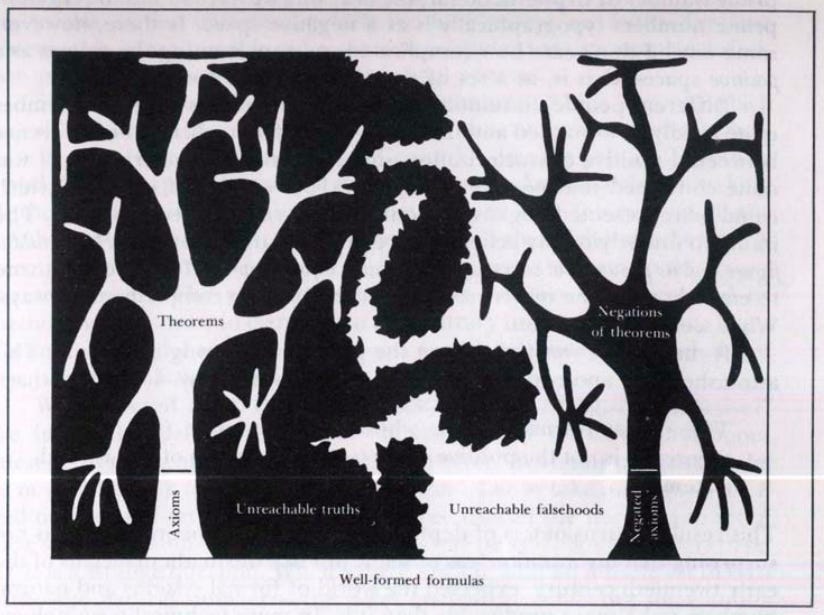

The above image is a Gödel-inspired diagram, popularized in Hofstadter’s Gödel, Escher, Bach, where axioms at the trunk produce theorems (reachable statements) branching outward, and large regions remain labeled as unreachable truths and unreachable falsehoods across the space of well-formed formulas. This picture is useful for LLM InfoSec because it shows why semantic leakage could be seen as a structural problem.

In this framing, the axioms are the system’s base information: training corpora, connected repositories, indexed RAG stores, tool-accessible data, and memories. The theorems are the set of reachable outputs: what the model can reliably produce from that base. As you add axioms (data sources), you expand the reachable theorem space. As the model becomes more capable, it can traverse more complex proof paths, meaning more joins, more inference chains, and more plausible reconstructions.

The legal and compliance bottom line is that under semantic integration, it is no longer safe to say we did not disclose X if the system can derive X from what it did disclose, or from what it was permitted to access in pieces. That is why CSS treats domain boundaries as something you must operationalize and test. If you cannot prove certain classes of statements remain unreachable, you do not have a boundary.

Ordinary Use Cases

Most semantic leakage is not going to begin with a state actor breaking airgaps. It begins with a normal person doing a normal thing. A user pastes sensitive text into a cloud LLM because it is the easiest way to draft, summarize, or translate something. The same convenience pattern shows up elsewhere: people paste internal fragments into Google queries, copy sensitive snippets into cloud notes, or drag documents into synced storage like OneDrive so they can work across devices.

The legal and InfoSec difficulty is that these acts can turn a local confidentiality obligation into a third-party processing event. Safeguarding classified or proprietary information does not usually mean trusting Google or OpenAI to safeguard classified information. It means you design systems so that the data never enters an ungoverned third-party plane in the first place, and you assume the default consumer workflow is not your security boundary.

OpenAI’s consumer-facing ChatGPT has multiple data modes that matter for risk analysis. Consumer ChatGPT content may be used to improve models by default, with user controls to opt out. Temporary Chats are described as not being used to train models. OpenAI also states that it does not train on API data by default, and that business offerings like ChatGPT Business and ChatGPT Enterprise are not trained on by default.

Even if a vendor policy is privacy-forward, the compliance reality remains: policies change, datasets get retained for abuse monitoring or legal holds, and breaches happen. This is why CSS includes a cloud prompting control family, not because consumer LLMs are uniquely evil, but because they are the most common ungoverned connector between protected domains and public model ecosystems.

Relevant Regulatory Frameworks

CSS will not be a privacy statute. It is a security and assurance standard meant to create a legible standard of care for information leakage and boundary erosion in LLM-enabled systems. That said, the standard is designed to be usable inside existing legal frameworks that already care about disclosure and confidentiality.

— HIPAA Security Rule (ePHI): requires reasonable and appropriate administrative, physical, and technical safeguards to protect confidentiality, integrity, and availability of electronic protected health information.

— 42 CFR Part 2 (SUD records): imposes strict limits on use and disclosure of substance use disorder treatment records; HHS emphasizes constraints on use in investigations and prosecutions without consent or court order.

— Deemed exports: under U.S. export controls, releasing controlled technology or source code to a foreign national inside the United States can be treated as an export to that person’s home country, which makes LLM-enabled collaboration and tool-assisted drafting an export-control surface, not just an InfoSec surface.

— GLBA Safeguards Rule (financial customer information): requires a written information security program with administrative, technical, and physical safeguards.

— FERPA (education records): restricts disclosure of students’ education records and PII without consent.

— GDPR principles (EU): include integrity and confidentiality and accountability, with purpose limitation and data minimization norms that become strained when prompts and logs become long-lived training artifacts.

— CCPA/CPRA (California): establishes privacy rights and interacts with breach and “reasonable security” expectations, including private right of action in certain breach contexts.

— FTC Act Section 5 enforcement posture (U.S.): FTC frequently uses Section 5 (unfair or deceptive acts) in privacy and security enforcement; for LLM deployments, “we had policies” without operational controls is the familiar failure mode.

— Trade secret law (DTSA/UTSA ecology): the existence of a trade secret partly depends on reasonable measures to keep it secret; uncontrolled LLM ingestion and uncontrolled cloud prompting can become evidence that secrecy measures were not “reasonable.”

— ITAR technical data: “technical data” definitions explicitly include classified information relating to defense articles; this matters when engineering teams paste controlled technical details into external tools.

CSS’s thesis is simple: these regimes already impose confidentiality duties, but they do not define what it means to prevent semantic leakage and domain infiltration. A GAAP-like standard for LLM InfoSec supplies that missing operational layer.

Some Existing Standards

Below is a map of existing frameworks and why they are useful, but incomplete, for semantic leakage and reachability risk.

NIST AI RMF 1.0

— What it is: Voluntary AI risk management framework (GOVERN / MAP / MEASURE / MANAGE).

— Strengths: Governance vocabulary, risk lifecycle, fits enterprise risk programs.

— Gaps CSS targets: Not an audit-ready control spec; does not prescribe leakage metrics or test harnesses.

NIST GenAI Profile (AI 600-1)

— What it is: GenAI-specific profile aligned to AI RMF.

— Strengths: Identifies GenAI risks and actions; helpful crosswalk anchor.

— Gaps CSS targets: Still action-oriented guidance; not a SOC-style attestation template with required evidence and thresholds.

ISO/IEC 42001

— What it is: AI management system standard (AIMS).

— Strengths: Auditable management-system structure; internationally legible governance.

— Gaps CSS targets: Management system does not equal leakage controls; does not define domain infiltration tests or metrics.

CSA AI Controls Matrix (AICM)

— What it is: 243 control objectives across AI security domains; mapped to ISO and NIST.

— Strengths: Control-matrix form is close to what CSS wants; already designed for adoption and mapping.

— Gaps CSS targets: Needs a leakage-specific measurement and adversary-testing layer; semantic reachability is not the organizing concept.

OWASP Top 10 for LLM Apps

— What it is: Threat list for LLM applications (prompt injection, sensitive info disclosure, etc.).

— Strengths: Concrete attack classes; useful for test suites and minimum mitigations.

— Gaps CSS targets: Not an assurance standard; does not define maturity levels, evidence catalogs, or audit sampling.

MITRE ATLAS

— What it is: Knowledge base of adversary tactics and techniques for AI systems.

— Strengths: Best source for adversary emulation grounding; supports red-teaming realism.

— Gaps CSS targets: Descriptive, not prescriptive; doesn’t tell you what “reasonable leakage prevention” is.

Google SAIF

— What it is: Conceptual framework with core elements for securing AI.

— Strengths: Useful secure-by-default framing.

— Gaps CSS targets: Not a disclosure or assurance artifact; does not define leakage metrics or standardized tests.

Most Feasible Adoption Path

Most feasible adoption path: CSS as a profile or assurance annex that plugs into CSA AICM control mapping and an AICPA SOC-style report structure, while grounding adversary testing in OWASP and MITRE ATLAS.